Bihar’s Flip-Flop on Alcohol Policy

Bihar’s Flip-Flop on Alcohol Policy

- Ghanshyam Sharma

- December 12, 2025

- Cultural Economics, Public Policy, State Economies

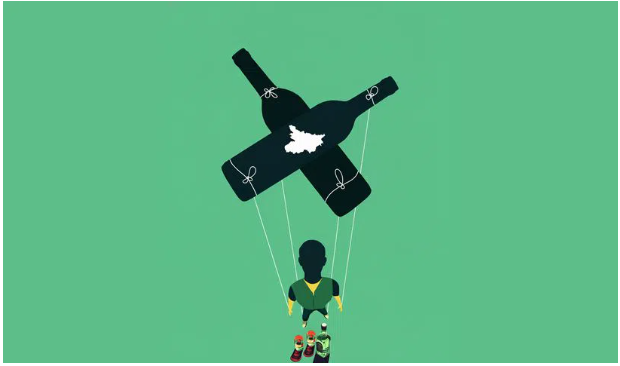

Ironically, the poorest and most corrupt state first increased the number of alcohol addicts by promoting alcohol sales. Then, it arrested over 13 lakh men – for drinking alcohol.

Ironically, the poorest and most corrupt state first increased the number of alcohol addicts by promoting alcohol sales. Then, it arrested over 13 lakh men – for drinking alcohol.

Over the past two decades, Bihar has conducted a uniquely absurd experiment in the history of alcohol regulation. Starting in 2006, it actively promoted the sale of alcohol to increase tax collections from alcohol sales. However, in 2016, it reversed course and introduced one of the strictest alcohol bans, which has had significant adverse effects on the people, corruption, and the economy.

After the 2005 elections, the Bihar government pursued a policy to open a theka (or liquor shop) in every panchayat. Media reports noted that the number of liquor shops in rural areas tripled, from 779 to 2,360. As a result, tax revenues from alcohol jumped from Rs 87 crore to Rs 3142 crores in 2014-15. This represented 15 percent of the state’s budget.

The new thekas increased the proximity to liquor. As a result, the number of men with alcohol addiction increased by 50 percent (NFHS-3 and 4). People develop an addiction to alcohol due to physical or emotional dependence on alcohol. For example, manual labourers drink alcohol to deal with chronic pain, especially in the absence of reliable and accessible healthcare. Similarly, people who have been exposed to childhood adversity or are dealing with mental health issues are more likely to turn to alcohol for relief. When access to alcohol improves, such people are likely to increase their frequency and volume of alcohol intake. Thus, the policy exploited the vulnerable groups prone to alcohol addiction to raise tax revenue.

However, despite the state government’s push to increase alcohol sales, the overall percentage of men in Bihar who drink alcohol actually declined in this period. The proportion of married women who reported that their husband drinks alcohol fell from 39 to 35 percent from 2006 to 2016 (National Family Health Survey-3 & 4). Hence, the alcohol taxes increased sales only because of an increase in demand from vulnerable groups who were prone to addiction.

Hence, when Bihar imposed a comprehensive ban on alcohol in 2016, it came as a policy shock because the fraction of men who drink alcohol in Bihar was already declining (despite the government promoting alcohol). Besides, relative to other states, fewer men in Bihar were drinking alcohol.

Several rigorous penal provisions of the prohibition law also came as a shock. For example, the provision of ‘guilty until proven innocent’ placed the burden of proof on the accused. According to the Transparency International Report (2019), Bihar is the most corrupt state in India. This law makes citisens vulnerable by vesting indiscriminate powers with the police to arrest people without proof. The law also punished drinking in a public place with life imprisonment. The law penalised possession of knowledge about alcohol with eight years of imprisonment.

The law has had several predictable consequences. Since 2016, Bihar has arrested over 13 lakh people (mostly men) under the prohibition law, as only half a percent of women drink alcohol in Bihar (NFHS). The actual conviction rate in these cases is one percent (Indian Express report). Kumar and Raghavan (2020) found that the SCs & STs faced disproportionate arrests under this law, and many have been awaiting trial for several years. Over 8 lakh prohibition-related cases have clogged the courts and overcrowded prisons. The prohibition has led to thousands of undocumented deaths from spurious alcohol.

In April 2023, the Supreme Court raised concerns about the fairness of the law that makes drinking alcohol a non-bailable offence. The Court also questioned whether the prohibition had been effective in curbing alcohol consumption. In a study recently published in the journal Economics of Governance, I find that despite such rigorous provisions, there has been only a 6 percentage point decline among men who drink alcohol. I also find empirical evidence for bootlegging. Alcohol consumption has declined less in districts that share a border with other states or Nepal. Selling alcohol in districts that do not share a border with other states would imply dealing with two police departments, which would increase the price and risk of selling alcohol in such districts.

I find further evidence of bootlegging as there is a sharper decline in low alcohol (e.g, beer) drinkers compared to high alcohol spirits (e.g., whiskey). This is because high-alcohol spirits such as whiskey are easier to store and last longer compared to low-alcohol drinks, which may need cold storage. I also find evidence of a decline in branded alcohol drinkers, but no decline in spurious alcohol drinkers. This could be because branded alcohol is imported from outside the state, while spurious liquor can be sourced locally. Branded alcohol is relatively less harmful to drink than locally made liquor. Bootleggers use methanol to increase the potency of unbranded liquor, which can have severe health complications such as blindness or death. The alcohol ban has resulted in thousands of undocumented deaths from the consumption of spurious liquor.

I also discovered that the prohibition has only deterred occasional drinkers – people whose frequency of alcohol consumption is less than weekly. The ban has not deterred people who drink daily. There is only a 1 to 2 percent decline in men who drink alcohol daily. This again highlights the wide availability of alcohol and the limitation of the policy.

Governments globally have realised that educating people is more effective than bans. For example, the US government had to reverse its alcohol ban in the 1930s. Several US states have recently amended their “War on Drugs” policy and legalised their use. Prohibitions only lead to black markets, unfair arrests, targeting of vulnerable groups, an increase in corruption, loss of tax revenues, and the strengthening of criminal gangs/mafia.

Bihar’s ban on alcohol has been a colossal policy failure. The ban is an attack on personal freedom. While alcohol is generally a health hazard, the freedom to choose includes the freedom to make bad choices and learn from them.

The author is Teaching as Associate Professor of Economics at RV University, Bengaluru.

The Author is also a Research Fellow at AgaPuram Policy Research Centre. Views expressed by the author are personal and need not reflect or represent the views of the AgaPuram Policy Research Centre.

This article was originally first published by https://telanganatoday.com/opinion-bihars-failed-war-on-alcohol-and-its-human-cost