GA Natesan: Liberal Scholar and Publisher

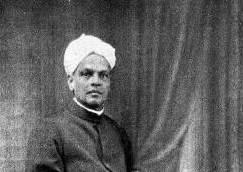

GA Natesan: Liberal Scholar and Publisher GA Natesan: Liberal Scholar and Publisher GA Natesan was the one who introduced Gandhi to Tamil Nadu and South India when Gandhi first visited Madras (now Chennai) in 1915 after returning from South Africa. It must be noted that C Rajagopalachari or Rajaji met Gandhi for the first time at GA Natesan’s home. For more than half of the century, Natesan was very close to Gandhi personally even before Gandhi returned to India. Still, he seldom agreed with his ideas and thoughts on politics and freedom struggles for varied reasons. Chandrasekaran Balakrishnan April 27, 2020 Indian Liberals For some pundits, it may not be so strange to take deep dive into history in distress to learn and understand the hue and cry of some of the current issues like the financial sector crisis in India or the Coronavirus pandemic. History is witness to great thinkers and scholars’ magnificent works which invariably help us to understand the history towards building better humanity in years to come but not without uncertainty. Alas, the epidemics of distorted history and some of the forgotten history of Indian economic thoughts have been the phenomenon for several decades even after the country’s independence. One of the forgotten classical liberal scholars and noted publisher in British India was Ganapathi Agraharam Annadhurai Aiyer Natesan in Madras Presidency. He was called GA Natesan by many and had played an immense role in the first half of the twentieth century in a different capacity. He was noted classical liberal scholar, writer, journalist, publisher, politician, freedom-fighter, and educationist. He was publisher of nationalist books, pamphlets, monographs, journals, biographies, speeches, and writings of eminent leaders both in English and Tamil languages at much lower prices for more extensive circulation intended towards the national awakening through informed debate and discussion. GA Natesan was the one who introduced Gandhi to Tamil Nadu and South India when Gandhi first visited Madras (now Chennai) in 1915 after returning from South Africa. GA Natesan was in contact with Gandhi since 1896 while he was studying in College in Madras. Gandhi stayed at his house from 17 April 1915 to 8 May 1915. It must be noted that C Rajagopalachari or Rajaji met Gandhi for the first time at GA Natesan’s home. For more than half of the century, Natesan was very close to Gandhi personally even before Gandhi returned to India. Still, he seldom agreed with his ideas and thoughts on politics and freedom struggles for varied reasons. After Gandhi’s revolutionary passive resistance movements embarked against British Raj, GA Natesan left the Congress Party. He became the First General Secretary of National Liberal Federation of India, a Liberal Party founded in 1918 by VS Srinivasa Sastri and other like-minded liberals who believed and fought freedom movements through constitutional methods as envisaged by MG Ranade and Gokhale. Natesan was Secretary of Madras Branch of Liberal Party from 1922 to 1947 and had played a significant role in promoting liberal ideas among the educated class. GA Natesan was born on 25 August 1874 in Ganapathi Agraharam village in Thanjavur district in Madras Presidency, now part of Tamil Nadu. He was schooled at Kumbakonam and went for his higher education at St. Joseph’s College in Tiruchirappalli. He completed his BA in 1897 from Presidency College, Madras. He lost his father when he was two years old and was brought up by his elder brother Vaidyaraman. The latter had a profound influence on him and sent him for higher studies to Glyn Barlow, an Irishman and well-known editor of Madras Times for an apprentice in journalism. After a short period, GA Natesan joined his elder brother Vaidyaraman in press and publishing activities and founded a company called GA Natesan and Co. in 1897 as proprietor. Soon, along with his brother, he started a monthly journal called the “The Indian Politics”, edited by him. The journal advocated the use of constitutional reforms to attain freedom. In 1900, GA Natesan started another monthly journal called “The Indian Review” which was published and edited by him for about five decades till his death in 1949. In a short period, the journal had become a voice of intellectuals on all significant public matters across India and England for its informative and instructive contents. The journal had literary reviews, illustrations, and sections on economy and agriculture among others. The journal had published materials on all major issue during the Indian Freedom struggle. It had a detailed analysis and included diverse opinions and commentary. Some of the early contributors to this journal were PS Sivasamy Aiyer, RC Dutt, Gokhale, CP Ramaswamy Aiyer, VS Srinivasa Sastri, V Krishnaswamy Aiyer, and Gandhi. The Indian Review had a highly praised editorial note by GA Natesan. The note provided a comprehensive review of all aspects of national progress, reflecting Indian thinking and ups and downs of the freedom movement. The journal was published continuously even after Natesan’s death till 1962 by his family and then through different hands, finally ending publication in 1982. GA Natesan was the first person to publish a book on Gandhi in 1909 titled MK Gandhi: A Sketch of His Life and Work by HSL Polak. The publication house of GA Natesan and Co. published any content that could awaken the educated class in India to achieve freedom from the British through constitutional methods. GA Natesan had published most erudite and thought-provoking articles and books for several decades. Apart from his publishing business, GA Natesan had a versatile personality, and he actively participated in the freedom movement and discussions with elected officials of local and national governments. GA Natesan was nominated as Non-Official Member to the Council of States in 1923. He also served another term up to 1931. During his tenure as a Member of the Council of State, he served as Member of the Indian Delegation to the Empire Parliamentary Association in Canada in 1928. He was also a member of the Indian Iron and Steel Tariff Board in 1933-34. GA Natesan served as Councillor in the Corporation of Madras

GA Natesan: Liberal Scholar and Publisher Read More »