B-R-shenoys-forgotten-voice-of-dissent

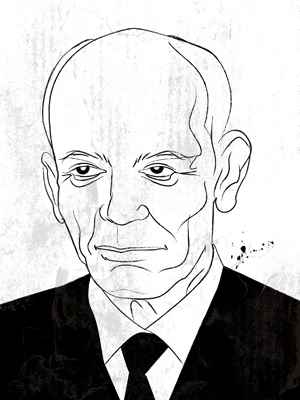

B.R.Shenoy’s Forgotten Voice of Dissent B.R.Shenoy’s Forgotten Voice of Dissent Chandrasekaran Balakrishnan July 29, 2011 Indian Liberals On a pleasant March day in 1963, Milton Friedman met US Ambassador J. K. Galbraith for lunch in New Delhi. The invitation from Galbraith read, “As you know, I do not agree with your ideas, but they will do less harm in India than anywhere else…” Even Galbraith — a great proponent of planning — recognised the relation between corruption and interventionism. Unfortunately, a great majority of India’s economists toed the Gosplan line. (Gosplan is short for Russia’s state committee for planning whose Five Year Plans continue to be a model for India.) B.R. Shenoy is the only Indian economist to write a note of dissent to the second Five Year Plan. Shenoy, India’s first monetary economist, thought that “the only hope of eradication of corruption on the current scale is a complete U-turn in our policies”. An ombudsman will not solve the problen of corruption in the world’s 10th largest economy, only more business freedom will. In February 1975, Shenoy delivered a lecture in Ahmedabad putting forward the thesis that interventionism is the root cause of corruption. Shenoy says corrupt payments arise because “a piece of paper which costs nothing, but the signature of the government official concerned to produce” has value. And it has value because government policy mandates acquiring licences, permits and quotas (LPQ) to run businesses. Data backs Shenoy’s theoretical ideas. There is a strong empirical relation between Heritage Foundation’s measure of ‘business freedom’ and Transparency International’s corruption index. In 2010, seven of the world’s 10 ‘least corrupt’ countries ranked amongst top 10 in ‘business freedom’: New Zealand, Singapore, Denmark, Canada, Sweden, Finland and Iceland. The 10 most corrupt countries have an average business freedom rank of 154, the 10 least have a rank of 12. India’s business freedom rank is 167!The Nordic countries from whom the concept of Ombudsman is borrowed, have an average ‘business freedom’ rank of 8. These countries do not have LPQ levers which bureaucrats could use to extract rents. According to the Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsmen Report for 2007-08, only one case ended in “prosecution and disciplinary proceedings”. The Ombudsman does fine-tune a well functioning system; it cannot fix a broken system like India. Unfortunately, the great Indian corruption debate is a battle between two camps of interventionists: Neither the government nor Team Anna realise that corruption is a consequence of entrusting few ‘wise’ men with too much, more of the same will not solve the problem. Shenoy, with his 1931 Quarterly Journal of Economics article, became the first Indian economist to publish in an academic economics journal. But India chose to ignore his critique of central planning. What followed was a tragic verification of his theoretical vision. (Vipin P. Veetil is doing his Ph.D. in Economics at Iowa State University. B. Chandrasekaran is in the Planning Commission, New Delhi) Facebook Instagram X-twitter

B-R-shenoys-forgotten-voice-of-dissent Read More »